Personal confession: The first time I heard about ulcers, I pictured some cartoon stomach bubbling with soda. Reality, as usual, is weirder and far more complex. Years later, after surviving a night of intense epigastric pain that I wrongly blamed on bad takeout, I realized just how much folklore and misunderstanding surrounds Peptic Ulcer Disease. Today, let’s unravel the odd truths, the missed signals, and a few quirky tales to bring this misunderstood stomach villain to life.

1. When Ulcers Crash the Party: More Than Just Indigestion

When most people hear “ulcer,” they picture someone doubled over from stress or blaming last night’s spicy curry. But here’s the truth: Ulcers aren’t always caused by stress or spicy food—that’s one of the biggest myths out there. The real story behind Peptic Ulcer Disease is far more interesting, and sometimes, more surprising.

“Most ulcers are not caused by stress, but by two very tangible enemies: Helicobacter pylori and NSAIDs.”

Understanding Peptic Ulcer Disease

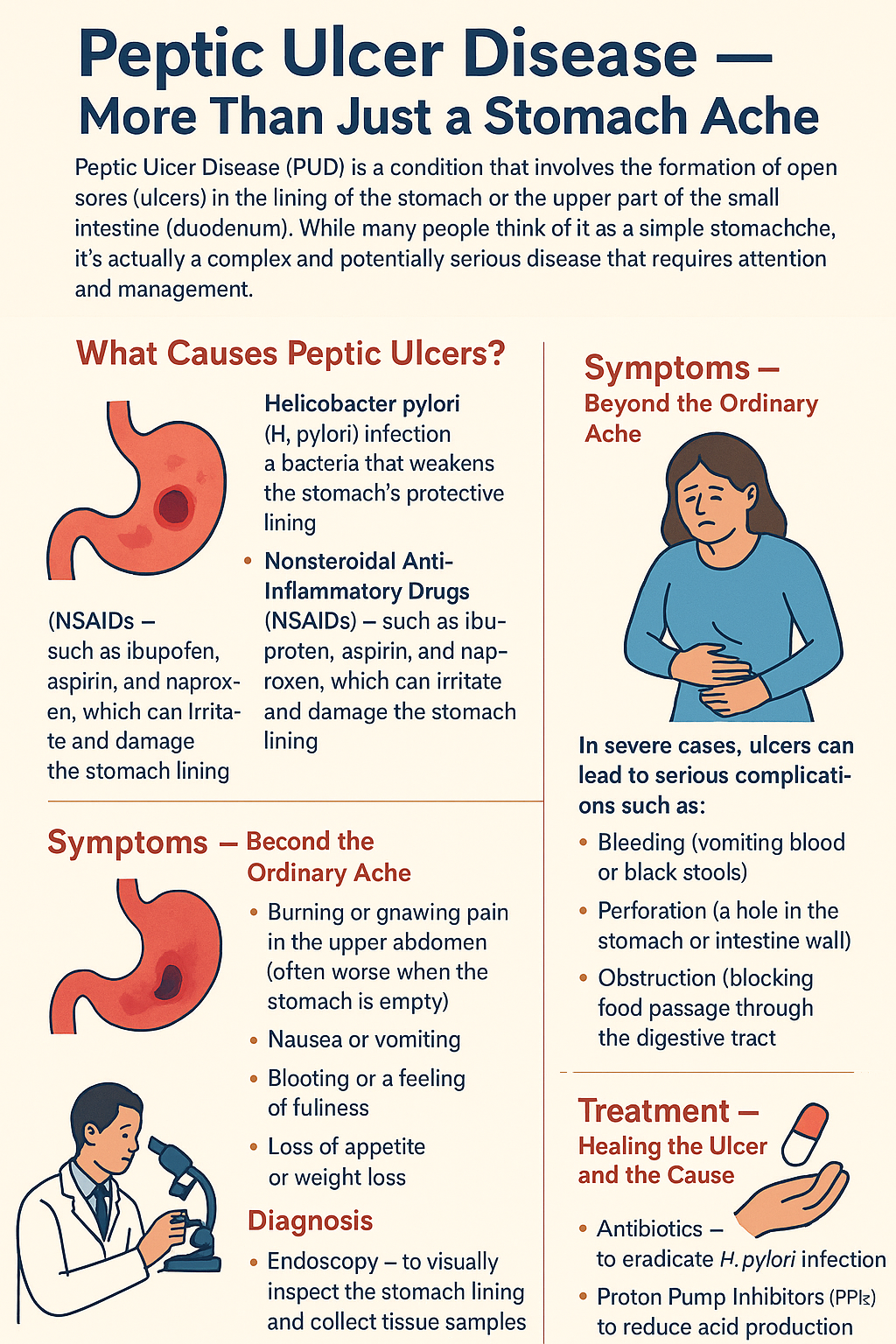

Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD) means you have one or more open sores—called ulcers—in the lining of your stomach (gastric ulcers) or the first part of your small intestine, the duodenum (duodenal ulcers). Oddly enough, duodenal ulcers are actually more common than gastric ones. These sores form when the protective lining of your digestive tract is damaged, letting stomach acid eat away at the tissue underneath.

The Anatomy of an Ulcer: What’s Going On Inside?

The inside of your stomach and intestines is lined with a special barrier called the mucosa. This mucosa is made up of three layers:

- Epithelial layer: The innermost layer, which absorbs nutrients and secretes mucus and digestive enzymes.

- Lamina propria: The middle layer, filled with blood and lymph vessels.

- Muscularis mucosa: The outermost layer, a thin band of muscle that helps break down food.

Different regions of the stomach have different types of cells and glands. For example, the cardia mainly secretes mucus, while the fundus and body produce acid and digestive enzymes. The antrum contains G cells that release gastrin, a hormone that tells the stomach to make more acid.

Causes of Ulcers: The Real Offenders

So, what actually causes these painful sores? Let’s break down the main culprits:

1. Helicobacter Pylori: The Bacterial Saboteur

By far, the leading cause of both gastric and duodenal ulcers is infection with a bacterium called Helicobacter pylori (or H. pylori). This spiral-shaped, gram-negative bacterium is a master at surviving in the harsh, acidic environment of the stomach. It attaches to the stomach lining, releases enzymes and toxins, and gradually damages the protective mucosa. Over time, this damage can lead to open sores.

Here’s a staggering fact: 70-90% of duodenal ulcers are linked to H. pylori infection. That’s a huge percentage! Interestingly, not everyone with H. pylori develops ulcers—some people carry the bacteria for years without any symptoms at all.

2. NSAIDs and Ulcers: The Painkiller Paradox

Another major cause of ulcers is the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen, naproxen, and aspirin. These medications are widely used for pain and inflammation, but they come with a hidden risk. NSAIDs block an enzyme called cyclooxygenase, which your body needs to make prostaglandins—compounds that help protect your stomach lining. Without enough prostaglandins, the mucosa becomes vulnerable, and ulcers can form, especially with long-term or high-dose use.

NSAID-induced ulcers account for a significant portion of all peptic ulcer cases, especially in people who use these medications regularly.

3. Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome: The Rare Culprit

In rare cases, Peptic Ulcer Disease is caused by a condition called Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome. This syndrome involves a tumor (gastrinoma) that produces excessive amounts of gastrin, a hormone that triggers the stomach to make more acid than normal. The extra acid overwhelms the mucosa’s defenses, leading to severe and recurrent ulcers. These tumors are usually found in the pancreas or duodenum.

Ulcer Myths: Stress and Spicy Food

Let’s set the record straight: Stress and spicy foods do not cause ulcers. While they can make symptoms worse or trigger discomfort if you already have an ulcer, they aren’t the root cause. The real enemies are H. pylori and NSAIDs.

Living with Ulcers: Sometimes, No Symptoms at All

Here’s something surprising: Not everyone with an ulcer feels pain. Some people walk around with ulcers and barely notice. Quick aside: I once met a runner who powered through half-marathons with a bleeding ulcer. Ouch—but true! This just goes to show that ulcers can be sneaky, and symptoms can range from mild discomfort to severe pain or even silent bleeding.

2. Symptom Detective: Why Ulcers Love to Play Tricks

When it comes to peptic ulcer disease, the symptoms can be surprisingly sneaky. You might expect a straightforward story—pain in the stomach, maybe some nausea, and that’s it. But the reality is, ulcers love to play tricks on us. The symptoms of ulcers can be confusing, unpredictable, and sometimes show up in places you’d never expect. Let’s break down what makes these symptoms so tricky, and why understanding the difference between gastric ulcers and duodenal ulcers is key.

Classic Clue: Epigastric Pain

The most common symptom of both gastric and duodenal ulcers is epigastric pain. This is an aching or burning sensation right in the upper middle part of your abdomen, just below the breastbone. It’s the pain that makes most people suspect something is wrong in the first place. But even this “classic” symptom isn’t always so classic.

- Some people feel a sharp, burning pain.

- Others describe it as a dull ache or just a sense of discomfort.

- Sometimes, the pain is mild and easy to ignore—until it isn’t.

But here’s where things get interesting: the timing of the pain in relation to meals can actually point to what kind of ulcer you might have.

Mealtime Mysteries: Gastric vs. Duodenal Ulcers

One of the wildest tricks ulcers play is how they react to food. It almost makes no sense—until you know the physiology.

- Gastric Ulcers: Pain increases during meals. When you eat, your stomach produces more acid and the food physically presses against the ulcer, making the pain worse. This often leads people with gastric ulcers to avoid eating, which can result in weight loss.

- Duodenal Ulcers: Pain decreases with food. Eating actually soothes the ulcer in the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine) because the food neutralizes some of the stomach acid. As a result, people with duodenal ulcers may eat more frequently to keep the pain at bay, sometimes leading to weight gain.

This meal-related pattern is one of the most helpful clues in telling the two types apart. But not everyone fits the textbook description, and sometimes, the symptoms overlap or don’t follow the rules at all.

Not-So-Classic Symptoms: Bloating, Belching, and Vomiting

While epigastric pain is the main symptom, ulcers often bring along some less obvious friends:

- Bloating: A feeling of fullness or swelling in the upper abdomen, even after eating only a small amount.

- Belching: Frequent burping can be a sign that your stomach is irritated.

- Vomiting: Sometimes, the pain or irritation is so severe that it triggers nausea and vomiting. In rare cases, if the ulcer causes a gastric outlet obstruction, food literally can’t get past the blockage, leading to persistent vomiting and even more severe symptoms.

Some people experience only these milder symptoms—no dramatic pain, just a bit of discomfort and digestive upset. That’s why ulcers can go undiagnosed for a long time.

Wildcard Symptom: Referred Pain

Here’s where things get really strange. Sometimes, an ulcer—especially a duodenal ulcer—can perforate, or create a hole in the wall of the intestine. When this happens, the pain doesn’t always stay in the abdomen. Because of the way our nerves are wired, pain from a perforated ulcer can actually show up in your shoulder. Yes, your shoulder.

“You’d think a stomach ulcer would only mean stomach pain, but sometimes, your shoulder gets involved. The body is wild like that.”

This is called referred pain, and it’s a reminder that the body’s warning signals don’t always make sense on the surface. If you ever have sudden, severe abdominal pain that radiates to your shoulder, it’s a medical emergency and needs immediate attention.

Summary Table: Ulcer Symptoms at a Glance

| Symptom | Gastric Ulcer | Duodenal Ulcer |

|---|---|---|

| Epigastric Pain | Worse with meals | Better with meals |

| Bloating/Belching | Common | Common |

| Vomiting | Possible, especially with obstruction | Possible |

| Weight Change | Weight loss | Weight gain |

| Referred Pain | Rare | Possible (shoulder pain if perforated) |

Ulcers are masters of disguise, and their symptoms can be as unique as the people who have them. That’s why being a symptom detective is so important when it comes to peptic ulcer disease.

3. Fighting Back: Diagnosis, Treatment, and a Few Urban Legends

When it comes to peptic ulcer disease, fighting back starts with getting the right diagnosis. If you’ve ever wondered how doctors can be so sure about what’s going on inside your stomach, let me introduce you to the wonders of upper endoscopy. This procedure, while not exactly a walk in the park, is the gold standard for diagnosing ulcers. During an upper endoscopy, a thin, flexible tube with a camera is gently guided through your esophagus, into your stomach, and sometimes into the first part of your small intestine (the proximal duodenum). This up-close look allows doctors to actually see the ulcer, which is far more accurate than guessing based on symptoms alone.

But the process doesn’t stop there. Usually, during the endoscopy, the doctor will take a small tissue sample—a biopsy. This isn’t just to confirm the ulcer; it’s also to check for any signs of cancerous (malignant) cells and, crucially, to test for the infamous Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. H. pylori is a spiral-shaped bacterium that’s been identified as a leading cause of peptic ulcers. Knowing whether it’s present is key to choosing the right treatment.

Once the diagnosis is clear, the next step is treatment. Here’s where the modern approach really shines. If H. pylori is found, the best results come from a combination of antibiotics (to kill the bacteria) and Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs). PPIs are powerful medications that reduce stomach acid production, giving your ulcer the chance to heal. This dynamic duo—antibiotics plus PPIs—has revolutionized ulcer treatment. In fact, most H. pylori-related ulcers are cured with this regimen, and the majority of people never need to worry about the ulcer returning if the infection is fully eradicated.

But what if H. pylori isn’t the culprit? Another major player in the ulcer world is the use of NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), like ibuprofen and aspirin. These medications can irritate the stomach lining and are notorious for causing ulcers, especially when used regularly or in high doses. If NSAIDs are to blame, the first step is simple but critical: stop taking them. Your doctor may also recommend switching to other pain relief options that are gentler on the stomach. Alongside this, PPIs are still the mainstay for healing the ulcer, as they create a less acidic environment and allow the tissue to recover.

It’s not just about medications, though. Lifestyle changes play a huge role in recovery and prevention. Substances like alcohol, tobacco, and even caffeine can worsen ulcers or slow down healing. Cutting back—or better yet, quitting altogether—can make a significant difference in your outcome. It’s one of those things that’s easier said than done, but your stomach will thank you for it.

Now, let’s address one of the biggest urban legends in ulcer care: the idea that surgery is the default solution. This couldn’t be further from the truth today. As I like to say,

“Once upon a time, surgery was the first stop for a bleeding ulcer—now, it’s a last resort.”

Thanks to advances in medical therapy, especially the use of PPIs and targeted antibiotics, surgery is rarely needed. It’s reserved for only the most severe cases, such as ulcers that don’t heal with medication, those that cause life-threatening bleeding, or when there’s a suspicion of cancer. For the vast majority, ulcers can be managed—and cured—without ever setting foot in an operating room.

In summary, the fight against peptic ulcer disease is more effective than ever. With accurate diagnosis through upper endoscopy and biopsy, targeted treatment with PPIs and antibiotics, and a focus on avoiding NSAIDs and other irritants, most ulcers heal without complications. The days of routine ulcer surgery are largely behind us, replaced by a smarter, safer, and far more successful approach. If you’re dealing with an ulcer, know that you have powerful tools on your side—and that a full recovery is well within reach.